Story Highlight

– Women struggle with medication safety during pregnancy decisions.

– Over 90% of medicines untested for pregnant women.

– WHO aims to improve drug testing for pregnant women.

– Historical Thalidomide scandal shaped current drug safety norms.

– New toolkit will support safe drug development for pregnancies.

Full Story

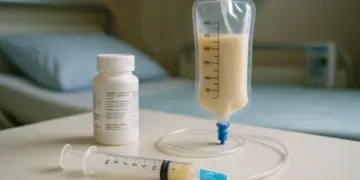

When Emma*, a 35-year-old living with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, made the decision to start a family, she faced a complex dilemma. The medications that had been crucial in managing her condition had to be carefully evaluated as she considered pregnancy. The challenges imposed by her illness, including severe complications that left her without a functioning bladder and reliant on nutrition delivered through a tube, further complicated her decision. Emma soon realised that reliable information regarding the safety of continuing her medications during pregnancy was scarce. “The vast majority of the information that’s available is like, ‘To be used if there’s no other options, no research done’. And without the medication, I will end up in hospital, so I don’t really have an option but to take it,” she expressed. The resulting uncertainty led her to experience intense feelings of guilt and anxiety.

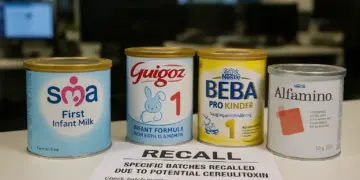

Emma’s story reflects a broader issue affecting a significant number of pregnant women worldwide. A staggering 90 per cent of medications lack testing for use during pregnancy, placing countless individuals in the troubling position of having to choose between necessary treatment and the unknown risks to their unborn children. In a noteworthy development, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has announced plans this year to collaborate with researchers, healthcare professionals, and pharmaceutical companies to address this gap—a significant step towards change reminiscent of the reforms following the Thalidomide disaster of the mid-20th century.

The Thalidomide tragedy, which arose in the 1950s, serves as a cautionary tale in this context. This medication, initially given to pregnant women for morning sickness, had not undergone testing for safety during pregnancy. It would subsequently be revealed that the drug could traverse the placenta and lead to severe birth defects affecting limb development. The aftermath of this scandal initiated the establishment of a rigorous drug safety monitoring system within the UK and the creation of the Medicines Act 1968, which mandated stringent testing procedures for pharmaceuticals.

However, pregnant women continued to be largely excluded from clinical trials, a practice deeply rooted in the hesitancy established by the Thalidomide experience. Mariana Widmer, a maternal health scientist at the WHO, states, “People have been scared to treat pregnant women since the Thalidomide tragedy, and pregnant women are scared to be treated.” She emphasises that effecting change in this realm requires a collective effort, noting, “There’s no one single organisation or one individual that can make this change. This change is huge. This takes time. We need collaboration and we need partnerships.”

The prevailing sentiment, shaped by the Thalidomide legacy, suggests that avoiding medication altogether is the safest course of action. Yet this mindset overlooks the fact that many pregnant individuals have chronic conditions requiring treatment. Health professionals often face the difficult task of communicating to patients that while some medications are necessary for their wellbeing, these drugs have not been adequately studied in pregnant populations. “They need to know that this medicine has never been tested in pregnant women,” Widmer states. This uncertainty poses a significant risk, as untreated chronic conditions can lead to maternal mortality, with chronic illnesses currently being a major contributor to maternal deaths globally.

Emma finds herself grappling with these conflicting imperatives. For instance, she relies on nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid used to relieve severe nausea and vomiting. “Before I had the [nabilone], I was in hospital every few weeks needing IV replacements and electrolyte replacements,” she recounts, explaining that continuing treatment is deemed safer due to the known consequences of discontinuing her medication. “It’s all being deemed safer that I stay on them because we know what’s going to happen if I don’t. And that’s probably more dangerous.”

The lack of rigorous trials supporting the safety of THC during pregnancy means much of the data available is derived from the behaviours of recreational cannabis users, complicating the already intricate assessment of risk. Additionally, the prospect of reducing her reliance on opioid painkillers was fraught with danger, as unmanaged pain could jeopardise her pregnancy. Emma articulates this precarious balancing act: “It’s this constant weighing up of what is more dangerous, what’s not more dangerous, and it’s really, really difficult to make that judgement.”

The WHO is set to evaluate essential medications for common chronic ailments in pregnant individuals, with the aim of developing guidelines that facilitate the safe inclusion of pregnant women in drug testing. A crucial aspect of this initiative will be to motivate pharmaceutical companies to prioritise the testing of these medications and engage with regulatory bodies to expedite their approval once validated.

According to Widmer, advancements in scientific understanding mean that we are not in the same position as when Thalidomide was first prescribed. “We have the means to know how to do it properly in order to ensure that the woman is safe and that the baby is safe,” she asserts. Current drug testing protocols involve a systematic approach, beginning with studies in laboratory settings and animal models, followed by trials in healthy adults, and then expanding to those with specific health conditions.

Dr Teesta Dey, who transitioned from delivering babies in the NHS to a role focused on global health, also highlights the challenges faced by pregnant women when navigating medication choices. Her own experiences during a complicated pregnancy revealed the lack of clear guidance available regarding the safety of various treatments. While speaking at a recent Birth Trauma Association event, she shared the frustrations faced by women uncertain about the appropriateness of medications. “So the reality of what happens is that people will take it off-label,” Dey explains, which places the burden of decision-making on women who often receive ambiguous advice from healthcare providers.

The Covid-19 pandemic further underscored the situation when a significant percentage of vaccine trials excluded pregnant and lactating women. Despite this, it became evident that the vaccines were safe, revealing the importance of including such populations in clinical studies from the outset. “We also know from the data that this was the population of women who had the poorest outcomes,” Dey notes, reflecting on the shortcomings of past research practices.

Moving forward, both Widmer and Dey advocate not only for safety but for the autonomy of pregnant women in making informed choices regarding their healthcare. They forewarn against a paternalistic approach that denies women the opportunity to participate in clinical research. Emma echoes this sentiment, expressing her willingness to engage in trials if presented with the option.

As part of ongoing efforts to address these issues, the WHO is preparing to launch a comprehensive toolkit this spring, aimed at supporting both researchers and patients. The conversation around treatment options during pregnancy is evolving, and the recognition of the need for inclusive research could pave the way for safer and more informed healthcare decisions.

*Name has been changed.

Our Thoughts

The article highlights significant gaps in drug testing for pregnant women, which contravene the principles of the Medicines Act 1968 requiring thorough safety evaluations before drug administration. To avoid situations like Emma’s, regulatory frameworks must include systematic testing of medications on pregnant women, ensuring they are not excluded from clinical trials. The “paternalistic model” that has historically restricted their participation must be challenged, allowing informed consent and empowering women to make decisions about their treatment options.

Key safety lessons include the imperative of balancing potential risks and benefits, which means changes in mindset within the medical community regarding pregnant women as valid participants in trials. Improvements in communication and clarity regarding medication use during pregnancy are crucial to reduce anxiety and guilt for women who must navigate treatment options amidst uncertainty.

To prevent similar incidents, collaborations among healthcare professionals, regulatory bodies, and pharmaceutical developers should be prioritized to formulate a comprehensive plan that includes the development of a toolkit to guide safe drug testing frameworks for pregnant populations, as proposed by WHO.