Story Highlight

– Mother fears winter worsening mould-related health issues.

– Son developed serious chest infection from mould disturbances.

– Council attempts repairs but fails to resolve damp issues.

– Over eight million in UK live in cold homes.

– Health Equals reports increased respiratory and mental health problems.

Full Story

A resident of Bristol has raised concerns about the health implications of living in a damp and mould-infested home as winter approaches. Tracy Manley, aged 59, has been living in her semi-detached house for nearly three decades, but it has only been in recent years that mould has become a significant issue. Manley first noticed dampness around her windows and subsequently found that items stored in the airing cupboard of her son’s bedroom were becoming damp as well.

As a mother and a tenant of Bristol City Council, Manley receives personal independence payments (PIP) and faces a worrying situation as the colder months approach. She believes that her attempts to address the mould issue inadvertently exacerbated her son’s health problems. Her son, who wishes to remain unnamed, experienced severe chest difficulties last winter which required medical attention and antibiotics.

“When we stripped the bedding last winter, he became ill and had to go on antibiotics,” she recounted. “There was a rattling on his chest. Initially, we were told by the doctor that it was clear, but then he started having trouble with his breathing.”

Ms Manley described the distressing situation further, stating, “He couldn’t walk across the living room without stopping for breath. It was a serious chest infection, and it was really bad. The doctor put him on a course of antibiotics for around 10 days.” Reflection on the situation led her to believe that the mould disturbance was the true issue; “It was a case of when it was disturbed that was the problem. You were disturbing the mould and then breathing in that disturbance. It was a bit scary; we hadn’t considered that possibility.”

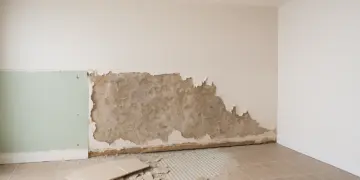

Photographic evidence presented by Ms Manley illustrates the extent of the mould problem in her home, showing patches proliferating around windows, on ceilings, and within the airing cupboard. Despite her efforts to treat the mould using chemicals, she found it challenging to eliminate the issue completely. “You’re always told to open the windows and to ventilate – we tried that, we tried the diffusers, the dehumidifiers,” she explained. “We left vents open, but it was a case of tackling it, clearing it away, but it was still coming back. That’s the problem; it seems to be an ongoing thing in the older houses.”

In addition to the health concerns affecting her son, Ms Manley also faces her own medical challenges. She was diagnosed with throat cancer last year and was undergoing chemotherapy during the time the mould was making its presence felt in her home. “I was worried about my own health, and it took a mental toll,” she said. “I’ve got a low immune system, and I’m on a course of chemotherapy. It was difficult to stay positive – it was draining on my mental health.”

Ms Manley is not the only individual grappling with similar issues. Health Equals, a campaign group, has estimated that over eight million people across the UK are living in cold homes. Their recent research indicates that 28 percent of the population encounters problems such as dampness and mould, conditions that have been linked to a variety of health issues. Moreover, the research reveals that a quarter of individuals residing in cold homes report experiencing respiratory symptoms, while more than one-third have noted adverse impacts on their mental health, including depression and anxiety.

With winter approaching, Ms Manley has voiced her fear regarding the potential aggravation of her son’s chest issues and the risk to her own health. Although Bristol City Council has responded to her pleas for assistance in the past, she remains skeptical about the long-term effectiveness of their interventions. “There’s still damp in my kitchen as well, and I’m worried about my son’s chest problem coming back this winter, as well as my own health. They’ve checked up in the loft, they’ve checked the guttering, and they seem to say there’s no problem with any of that, so it’s just tackling it as it comes on,” she expressed. “You’ve got to clean it, but you’re worried about making it worse for yourself. Then it gets airborne.”

Barry Parsons, chair of the council’s homes and housing delivery committee, responded to Ms Manley’s concerns, assuring that the council prioritises the health and safety of its tenants. “Our priority is to ensure all council homes are safe, warm, well-maintained, and meet the standards required of us as a social landlord,” he stated. “Since our self-referral to the regulator of social housing, we have been working hard to improve the way we manage and maintain our housing stock. Significant progress has already been made; since August, the number of open damp and mould cases has fallen significantly. However, we recognise there is still more work needed to ensure our homes meet the standards tenants deserve. We will continue to invest in the safety and quality of our homes with a strong focus on tackling damp and mould.”

Parsons further emphasised the importance of addressing every report of damp or mould effectively, undertaking to respond within ten working days. He encouraged tenants like Ms Manley to continue reporting these issues so that solutions can be pursued.

The council’s officers visited Ms Manley’s property last week to assess the ongoing problems and implement necessary treatments. As winter looms, both Ms Manley and the council are keen to find a resolution, but navigating an effective solution remains a persistent challenge.

Our Thoughts

The case highlights several key failures in health and safety obligations under UK legislation, particularly the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) and the duty of care expected from landlords under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985. The ongoing damp and mould situation in Ms. Manley’s home suggests systemic issues that should have been proactively addressed by the council, such as conducting regular inspections and ensuring adequate ventilation and moisture control in compliance with the Housing Act.

To prevent similar incidents, regular maintenance checks should have been mandated to identify and rectify underlying causes of dampness before they become health hazards. Additionally, providing tenants with clear guidance on safely managing mould and ensuring safe removal procedures could mitigate health risks.

Finally, training for council staff on the health implications of mould and the importance of timely intervention could enhance responsiveness to tenant concerns. Overall, a more comprehensive approach to property maintenance, combined with effective communication, is crucial to prevent such public health risks in social housing.