Story Highlight

– Additives in processed foods may harm gut microbes.

– High gut microbial diversity linked to better health outcomes.

– Emulsifiers found in many supermarket products affect microbiome.

– Ultra-processed diets lead to lower gut diversity.

– Cooking from scratch recommended for better health.

Full Story

The use of additives in processed foods, while designed to enhance preservation, may inadvertently affect the health of the gut microbiome—a complex community of microorganisms that plays a vital role in human health. Evidence suggests that alterations to this microbiome, particularly through the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs), might have significant health repercussions.

The microbiome, home to trillions of microbial cells, is essential for various bodily functions, influencing aspects ranging from mental well-being to metabolic processes. As noted by Melissa Lane, a nutritional epidemiologist at Deakin University, “You can think of gut diversity as like a forest. The more microbes you have and the different types of microbes in your forest, the greater resilience you have to any perturbations.” Research demonstrates that a diverse gut microbiome contributes to overall health, correlating with positive outcomes such as improved mood and longer life expectancy. In contrast, individuals with reduced bacterial diversity in their guts often experience sleep disturbances, inflammation, and compromised gut health.

Sarah Berry, a professor of nutrition at King’s College London, asserts, “It’s this whole ecosystem. It’s like an extra organ that we have in our body.” However, the rising consumption of certain foods, particularly ultra-processed options laden with additives, is raising concerns about their potential harmful effects on this delicate ecosystem.

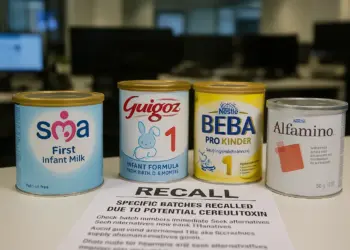

Additives such as dietary emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and food colourings are prevalent in many supermarket items, serving various purposes like enhancing flavour, improving texture, and extending product shelf life. For instance, a common chicken salad available in grocery stores may contain multiple emulsifiers, which allow oil and water to blend, contributing not only to taste and mouthfeel but also to the preservation of the product.

The ubiquity of emulsifiers is stark; research indicates that approximately half of the items analysed in UK supermarkets contain these additives, with some estimates reporting over 6,600 food products containing emulsifiers. However, potential health implications from these substances are concerning, as studies link emulsifiers to various gastrointestinal disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and colorectal cancer.

In animal studies led by Benoit Chassaing at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, exposure to low doses of common emulsifiers resulted in detrimental shifts in gut bacterial populations, propelling bacteria closer to the gut lining and leading to inflammation. Chassaing elaborates that the gut’s protective mucus layer typically keeps microbes at bay, and when this barrier is compromised, it can trigger chronic inflammatory diseases.

Correlational studies involving human participants echo the findings from animal studies. A large-scale French study involving over 100,000 adults revealed that increased exposure to emulsifiers correlated with a heightened risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Another investigation involving about 90,000 adults indicated a potential association between emulsifiers and certain cancers, such as breast and prostate cancer.

Further investigation by Chassaing and colleagues revealed that healthy individuals consuming emulsifiers commonly used as thickeners exhibited subsequent disruptions in their gut microbiota, reducing the prevalence of beneficial microbes.

In a clinical trial, Kevin Whelan, a professor of dietetics at King’s College London, collaborated with Chassaing to further investigate dietary impacts on individuals with Crohn’s disease. The trial illustrated that participants who adhered to a diet low in emulsifiers were three times as likely to report alleviated symptoms compared to those consuming a regular diet loaded with emulsifiers.

Despite the alarm raised by these findings, public guidance on avoiding emulsifiers is limited. Whelan notes the sheer number of additives in foods complicates efforts to assess their collective toxicity, stating, “Many [additives] have been classified as safe, but the interplay among various additives has not been adequately studied.” He emphasises that while emphasizers have passed industry toxicity regulations, they were never tested for their impacts on the microbiome.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) stipulates that all food additives within the European Union must receive proper safety evaluations, denoted by an E number. Meanwhile, in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) similarly mandates pre-market approval for food additives.

However, Chassaing points to the possibility of cumulative effects. The “cocktail effect,” as it is termed, highlights the complexities of studying the interaction among multiple additives, revealing that their collective impact may be more harmful than individual assessments suggest. Early-stage laboratory experiments involving human cells indicate that combinations of prevalent food additives potentially lead to increased cellular damage.

Moreover, the method of food processing itself may play a significant role in influencing gut health, beyond mere nutritional content. Recent studies have identified contrasts in gut microbiome diversity linked to dietary patterns. A randomised controlled trial led by Lane observed two groups consuming low-calorie diets over three weeks, one group relying predominantly on highly processed meal-substitutes, while the other opted for minimally processed foods. Although both groups lost weight, their gut bacteria showed marked differences; the low-UPF group displayed higher microbial diversity, while the high-UPF group exhibited reduced diversity and more gastrointestinal issues such as constipation.

Lane hypothesises that variations in gut health may stem from differences in fibre intake; the lower UPF diet provided a broader range of fibres derived from whole foods and contained fewer additives compared to the highly processed diet.

Experts suggest that beyond avoiding emulsifiers and UPFs, focusing on cooking from scratch with fresh ingredients can significantly benefit public health. Berry asserts that while eliminating ultra-processed foods entirely may not be realistic for everyone, it is crucial to encourage healthier eating habits. Whelan concurs, highlighting that moderation and a balanced approach to diet can promote overall wellbeing.

In short, increasing the intake of fresh produce while being mindful of food additives may support the health of our microbiome and enhance general health outcomes.

Our Thoughts

The discussed article highlights potential health risks associated with emulsifiers in ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and their negative impact on gut microbiome diversity. To prevent these issues, improved regulatory frameworks concerning food additives could be established under existing UK legislation, such as the Food Safety Act 1990 and the Food Safety and Hygiene (England) Regulations 2013.

Key lessons include the need for more stringent evaluation of food additives, specifically focusing on their long-term effects on gut health and microbiome diversity. Regulatory bodies should enforce comprehensive testing of not only individual additives but also their combined effects, addressing the “cocktail effect.”

Furthermore, public guidance about the consumption of emulsifiers and UPFs could help raise awareness and promote healthier dietary choices, aligning with the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 that emphasizes ensuring the health and safety of consumers.

To minimize similar incidents, promoting a shift towards minimally processed foods and educating the public on the importance of dietary diversity could enhance overall gut health, ultimately fostering a safer food environment. Implementing these measures can help avert significant health problems in the future.