Story Highlight

– Chimamanda Adichie’s son died due to alleged medical negligence.

– Lagos government launched an investigation into the incident.

– Aisha Umar died after scissors were left in her abdomen.

– Nigeria faces a severe shortage of healthcare professionals.

– Public outcry calls for urgent reforms in healthcare system.

Full Story

A series of tragic incidents involving alleged medical negligence in Nigeria has sparked significant public debate about the safety of patients and the broader failings within the country’s healthcare system. Notably, the recent death of 21-month-old Nkanu Nnamdi, the son of renowned author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, has drawn widespread attention and concern.

According to Adichie’s family, her son passed away last week in a private Lagos hospital after a brief illness. They claim that he was not provided with adequate oxygen and was excessively sedated, which ultimately led to a cardiac arrest. In response, the hospital expressed its “deepest sympathies” but firmly denied any allegations of wrongdoing, asserting that their medical practices adhered to international standards. Consequently, the Lagos State Government has initiated an inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the child’s death, amidst growing anger over the quality of healthcare in Nigeria, which is Africa’s most populous nation.

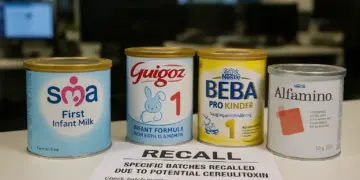

Compounding this outrage, just days later, the story of Aisha Umar in Kano surfaced, a mother of five whose family alleges medical negligence led to her tragic death. Following surgery in September at the Abubakar Imam Urology Centre, the family claims surgical scissors were inadvertently left inside her abdomen. After experiencing severe pain for four months and receiving only pain relief, scans eventually revealed the medical instrument. Her brother-in-law, Abubakar Mohammed, confirmed to the media that the family plans to pursue legal action against the hospital for negligence. In light of these claims, the Kano State Hospitals Management Board has suspended three staff members directly linked to the incident and has vowed to prevent negligence across state health facilities.

These incidents have resonated deeply, reflecting widespread frustrations among the Nigerian populace regarding the healthcare system. Josephine Obi, a Lagos-based product manager, recounted her own family’s distressing experience in 2021, when her father died following a surgical error at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Despite the procedure being deemed routine for a goitre, complications arose when a major artery was cut. Obi reported that a supervising doctor admitted the mistake, yet her family opted against pursuing a lawsuit, fearing the financial and emotional toll of a long legal battle. “You will just waste money and the case will linger… we just let it go,” she shared.

The tragic story of Ummu Kulthum Tukur further highlights the dire state of healthcare in Nigeria. Three years prior, her husband, Abdullahi Umar, lost her during childbirth at the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital. He believes that had a timely Caesarean section been performed, she might have survived. “She was in labour for over 24 hours… she lost a lot of blood and died,” Umar lamented, indicating that the hospital has since denied his requests for a death certificate.

These narratives of loss underscore a troubling reality within Nigeria’s healthcare landscape. Joe Abah, a former director of the Bureau of Public Service Reforms, also shared his own encounter with a private hospital in Abuja, which urged him to undergo immediate surgery for an ailment. After seeking additional opinions, including consultations abroad, it became apparent that surgery was unnecessary. This concern about treatment quality, although less frequently aired in private facilities, raises alarm bells. While private hospitals generally enjoy a better reputation, they remain out of reach for many Nigerians due to their high costs.

Dr. Fatima Gaya, a public hospital doctor, outlined a harsh truth: “Private hospitals are out of the reach of many Nigerians because they are expensive but without doubt offer better care compared to government-owned hospitals which carry more load and have manpower and equipment issues.” This disparity is compounded by the fact that many wealthy individuals, including high-ranking officials, often seek medical treatment overseas.

Dr. Mohammad Usman Suleiman, president of the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors (NARD), pointed to systemic issues rather than individual negligence as the root of these failures. He explained, “Clinical governance needs to be stepped up. In Nigeria, what we have is individuals being blamed for a systemic problem.” His insights resonate with emerging data: surveys conducted last year indicated that approximately 43% of Nigerians had either experienced or witnessed medical errors, with a substantial proportion suffering further injuries due to treatment mishaps.

The chronic shortage of healthcare professionals and outdated medical facilities exacerbates the problem. A significant exodus of doctors has plagued the sector, with the Nigerian Medical Association estimating that about 15,000 doctors have left the country in the past five years. As a result, the doctor-patient ratio has become alarming, with one doctor now serving roughly 8,000 patients, a stark contrast to the recommended ratio of 1:600.

Public affairs analyst Ibrahim Saidu emphasized that this staffing imbalance drives up workloads and stress among healthcare workers, inevitably leading to medical errors. “An imbalance of over 8,000 patients to one doctor increases overload and stress, which leads to mistakes,” he stated, reinforcing the perception that the healthcare system is failing its citizens.

Nigeria’s health system is further beleaguered by inadequate funding, with the federal government allocating a mere 5% of its budget to health. This is far below the 15% target established by the African Union in 2001, aimed at enhancing medical services across the continent. The recent tragic cases have intensified calls for urgent reforms to Nigeria’s healthcare sector to prevent others from suffering similar fates and to address the deeper issues that have long afflicted this vital area of public life.

Our Thoughts

The article highlights severe issues of medical negligence in Nigeria’s healthcare system, leading to preventable deaths. Although UK health and safety legislation does not directly apply, the article illustrates vital lessons relevant to maintaining patient safety.

To avoid such tragedies, healthcare facilities must adhere to strict clinical governance standards, ensuring compliance with the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, which mandates the provision of safe care and adequate staff training. Essential practices include a rigorous checking system for surgical instruments to prevent incidents like leaving tools inside patients, as occurred in Aisha Umar’s case.

Moreover, the NHS constitution emphasizes the importance of informed consent and improved communication between healthcare providers and patients. Enhancing staffing levels and reducing patient-to-doctor ratios, as required under the Care Standards Act 2000, could alleviate staff burnout and minimize errors.

Lastly, regular training and evaluations aligned with the Regulated Activities Regulations 2014 would better equip healthcare professionals to adhere to safety standards and improve patient outcomes. Establishing a culture of accountability and transparency is crucial in addressing systemic failures in healthcare systems.