Story Highlight

– UK and FDA introduce strategies to phase out animal testing.

– FDA aims to streamline non-clinical programs for antibodies.

– Emphasis on New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in drug development.

– Shortened toxicology study timelines could lower development costs.

– Shift towards human-relevant methods aims to improve drug safety.

Full Story

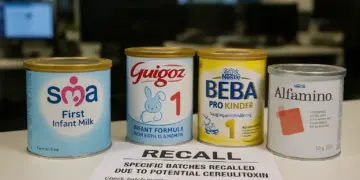

In November 2025, a significant shift occurred within the UK government as it unveiled a comprehensive plan to phase out animal testing, which was outlined in the “Government Strategy and Roadmap.” This policy initiative marks a pivotal moment in the way safety and efficacy for new drugs are evaluated, especially before commencing clinical trials involving human participants. The announcement closely follows similar measures from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has also initiated its own roadmap aimed at reducing or ultimately eliminating animal testing for specific pharmaceuticals.

As the UK is steering towards an era where animal-based clinical trials are no longer the norm, it is vital to assess the implications of these changes on a global scale, particularly by observing strategies adopted by other regions and regulatory bodies. The FDA’s renewed focus on developing alternatives to traditional animal testing is expected to reshape non-clinical development over the next three to five years significantly.

Recent FDA initiatives, including the Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies and the draft guidance on monoclonal antibodies, indicate a strategic pivot towards minimising the use of non-human primates (NHPs) and other animal species in drug testing. This strategic shift is rooted in the FDA’s commitment to the three Rs—reduce, refine, and replace—and is supported by remarkable scientific progress in developing human-relevant New Approach Methodologies (NAMs).

The changes proposed are expected to transform the economic, operational, and scientific dimensions of preclinical safety assessments, with profound effects on the timelines and financial aspects of drug development, as well as the comprehensive strategy behind clinical trials.

A key driver behind the FDA’s moves is the growing awareness that traditional animal models often fail to accurately predict human outcomes. The FDA’s findings reveal that over 90% of drugs that show promise in animals do not perform well in human trials, primarily because the safety and efficacy indicators observed in animals frequently do not translate to human biology. The FDA’s recent draft guidance underlines a focus on monoclonal antibodies, suggesting that adverse reactions are often linked to exaggerated pharmacological effects rather than off-target interactions. This scientific understanding facilitates a refined, streamlined approach to non-clinical testing.

Key recommendations proposed in the latest draft guidance include limiting long-term toxicity assessments in non-rodent species to situations where they are absolutely necessary and encouraging the integration of robust weight-of-evidence (WoE) evaluations that incorporate various data types, including mechanistic biology and pharmacokinetic profiles. The guidance also suggests that when previous animal data has demonstrated a lack of predictive value for human responses, it may not warrant consideration in future studies.

The FDA’s roadmap further articulates its ambition to position animal studies as a last-resort option rather than a standard requirement within non-clinical safety evaluations. This transformation aims to be achieved within a three to five year timeframe and encompasses both immediate and long-term actions.

In the short term, FDA initiatives may include reducing six-month toxicology studies in non-human species to three months when justified, encouraging the submission of both NAM and animal-derived data in parallel, and exploring scenarios in which animal studies can be waived in favour of NAMs. Furthermore, the FDA seeks to create an international toxicity database accessible to researchers to collaborate effectively on predictive models.

For longer-term outcomes, the FDA aims to establish NAMs as the standard practice for toxicological evaluation, reserving animal testing solely for situations in which these methods fall short in answering specific scientific questions.

The introduction of these initiatives may bring about considerable reductions in the time and resources dedicated to preclinical studies. With the new framework, preclinical safety assessments for monoclonal antibodies could be significantly abbreviated, as fewer studies may be required—and in certain instances, even omitting animal studies entirely if a relevant species is not available for testing. Scientific tools such as organs-on-chips and computational models are expected to enable quicker turnaround times, potentially allowing for the identification of human-specific safety issues more rapidly than traditional methods.

The implications of these recommendations may open the door to substantial cost savings, particularly in the development of monoclonal antibodies. By decreasing the frequency of six-month non-human primate toxicology assessments, substantial savings can be achieved while also alleviating pressures associated with the availability of such animals. Although initial investments in NAMs may be required, the long-term benefits, including enhanced predictive capabilities and reduced late-stage failures, are seen as compelling reasons to transition away from traditional models.

The FDA’s approach underscores a modernisation of the development strategy that may allow for faster approvals of new medications and greater adaptability in trial designs. Clinical safety and pharmacokinetics could be assessed with greater efficiency, and mechanisms to monitor biomarker responses could further enhance early trial phases.

Furthermore, sponsors who adopt NAMs proactively during the development stages are likely to present a strong case for the minimisation of animal testing. By effectively combining biological data, NAM insights, and clinical comparisons, developers can align with the FDA’s emphasis on a robust weight-of-evidence framework, ultimately advancing their projects through regulatory processes more swiftly.

The emergence of the FDA’s evolving framework represents more than just procedural updates; it signifies a transformative shift towards a framework prioritising human-relevant science in drug development. As the FDA seeks to reduce dependence on animal testing and embrace alternatives, opportunities abound for developers willing to adapt swiftly to these new methodologies, leading to more ethical, efficient, and scientifically sound pathways to market for novel therapies.

Our Thoughts

The article discusses the UK government’s strategy to phase out animal testing, reflecting a significant shift towards alternative methods in drug development. To avoid potential issues arising from this transition, several measures should be considered.

1. **Regulatory Compliance**: Adherence to UK legislation such as the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, which governs the use of animals in research, is crucial. The introduction of alternative methodologies must comply with ethical and scientific standards.

2. **Risk Assessment**: Implementing thorough risk assessments prior to trialing new methodologies will ensure safety concerns are addressed. This aligns with the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, which mandates assessing risks to employees and participants.

3. **Training and Education**: Offering comprehensive training on New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for developers can improve understanding of their application and reliability, which is essential for safe drug development.

4. **Stakeholder Engagement**: Early engagement with regulatory bodies can facilitate smoother transitions to alternative methods, providing clarity on approvals and guidance on best practices.

5. **Monitoring and Evaluation**: Continuous monitoring of the outcomes of non-animal testing methods is required to ensure safety and efficacy, consistent with the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999.

These steps can help mitigate risks associated with the shift away from animal testing and ensure compliance with health and safety regulations.